![]() This post originally appeared on the Unsettling Scientific Stories project blog

This post originally appeared on the Unsettling Scientific Stories project blog

At the end of March I went to my first science fiction convention: EasterCon. Also known as the British National Science Fiction Convention, now in its 67th year, the convention is given a name that reflects its location or theme each year and for the Manchester EasterCon we had Mancunicon (for the 2018 convention, being held in my hometown of Harrogate [North Yorkshire, UK], we have FollyCon – I have high hopes for lots of Victorian folly and steampunk revelry!). The convention, which is primarily literary, was drastically different from my convention expectations of cosplayers and comic books. It was a serious and engaging event where, as a SF researcher, it was great to speak to a huge range of writers, fans, and commentators. Audience questions were perceptive and revealing and I found the entire experience very rewarding.

I was on a panel organised by Manchester independent press Comma Press called ‘(Don’t) Ask a Scientist’. It consisted of computer scientist Prof. Susan Stepney (University of York), historian of science Dr Sam Robinson (Unsettling Scientific Stories, University of York), and me as the film studies and science communication scholar representing the Science and Entertainment Laboratory (University of Manchester). The panel allowed for discussions of SF across a range of storytelling platforms and for some interesting debate of how science and fiction interact.

To open the panel our chair Ra Page (Comma Press) asked us to identify good and bad examples of science in SF, which was a great way to start, as it gave me the chance to talk about why ideas of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ science isn’t all that helpful (or interesting, to me at least). Although I support the development of better science in science-based entertainment (book, film, TV, theatre…) I do not think that picking apart science mistakes is a particularly useful exercise – it’s far more useful to think about why the science is flawed and how it could be improved.

For my ‘good’ science example I talked about Spielberg’s adaptation of Jurassic Park (1993), and the film’s presentation of theories about the link between dinosaurs and birds (take a look at David A. Kirby’s work on science consultants including JP’s Jack Horner) and the impact the movie had on driving DNA research. For my ‘bad’ example I talked about one of my favourite early SF movies: the 1929 German silent Frau im Mond/Woman in the Moon. It’s a fantastic melodramatic spectacle with some impressive early special effects, but it also includes a lovely walk on the Moon without helmets (or death) – the explorer wears a spacesuit when he first lands on the Moon, but removes it when he ‘discovers’ that there is oxygen (#fail). But in its defence it also includes some very accurate predictions for the science of launching a rocket decades before Apollo 11 got to the moon. Director Fritz Lang consulted with Germany’s foremost rocketry expert, Herrman Oberth, in order to envisage what would be needed to get into space. Although the film includes a very clear example of incorrect, or ‘bad science’ it is important to remember that it is a movie from 1929 working with the research and knowledge available at the time.

The future just isn’t what it used to be! Imagined futures and the expectations for science change in accordance to the period of production. Science fiction (regardless of its creative form) is a reflection of the time in which it was made, even if it is attempting to predict the future of science and technology. I have recently moved from working on the project ‘Playing God: Bioscience, Religion, and Entertainment Media’ at the University of Manchester (but obviously still working on the blog!) to the Unsettling Scientific Stories Project at Newcastle University. Both of these fascinating projects engage with the idea of how different audiences receive and appropriate stories about science. Science on screen, page, and stage can have direct influence over how publics understand scientific ideas, practices and ethics, which can in turn affect policy decisions, attitudes to real world science, and future scientists who have consumed and been inspired by science-based fiction. SF can imagine futures and technologies that don’t exist yet and even give avid reader/viewer a sort of ‘past shock’ (rather than ‘future shock’) – where new technology seems old because it appeared in stories you’ve read and internalised years before it becomes reality.

SF gives use the opportunity to work through issues with science and futures before they actually happen – it’s a creative space that allows us to imagine both positive and negative consequences of our ever progressive technologies. Fiction can be used as a means of exploring emergent scientific ideas and exposing them to broader publics.

One of the major concerns for the audience was the idea of accuracy and whether authors had a responsibility to use accurate science. We talked about how science can be incorporated into science fiction novels through individual research and education, and also by collaborating with science practitioners. We discussed that readers/audiences are willing to suspend disbelief for science fiction – but that when the author pushes it to far it can throw people out of the narrative. We suggested that writers, therefore, have a responsibility to tell an honest and entertaining story, and that there is a difference between making an honest attempt and achieving flawless scientific accuracy. We settled on the idea that writers don’t have a responsibility to get the science right but instead have a responsibility to try not to get it wrong.

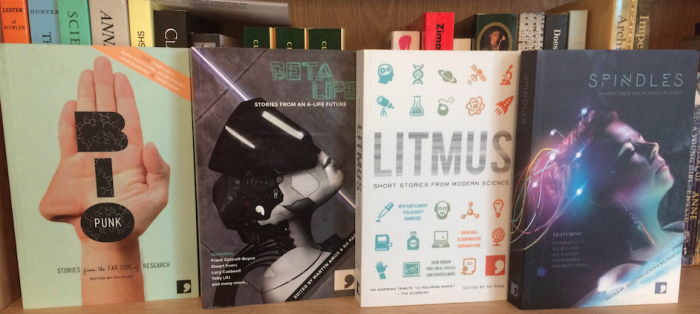

Science in fiction will rarely be perfect but good science can make for a better story, as Susan Stepney remarked, the reality of science is often more complicated and exciting than anything that can be made up. Comma Press have commissioned short story anthologies where scientists and creative writers have worked closely together to create stories. In the creative process of Litmus: Short Stories from Modern Science (2011) scientists put forward story ideas and authors worked with them to create a new piece of fiction. Once the story was finessed by the writer, the scientists were given the opportunity to essentially science-check the content and produce a commentary (postscript) reflecting on the story, its science and the process of working with a creative writer. It gave writers access to experts but also an opportunity to explore the mind of the scientist as well as their procedural and expert scientific knowledge.

We also debated whether a SF narrative could ever have too much science. Crime fiction and specifically crime procedurals seem to have unrestricted science with readers devouring the science-heavy work of contemporary investigators. But in science fiction there seems to be a limit where science might overwhelm the story. But there is a changing culture of how science is viewed in SF and how it can be seen to genuinely enhance a story and make it more entertaining. Accurate science can create restrictions but the process of working around and creatively through these problems can generate some pretty spectacular stories and storyworlds. So in discussions of science and fiction it is not simply about whether the science is ‘accurate’ but rather if it is entertaining.

Further Reading:

For some excellent further reading take a look at Susan Stepney’s Guardian article on The Real Science of Science Fiction.

I am now also blogging for my new project at Newcastle University whilst still producing content for the SciEntLab. I have loved blogging for this site and hope to be able to keep posting on science and entertainment. You can read my Unsettling Scientific Stories post here.

Many thanks to Ra Page at Comma Press for inviting me to speak on this panel. I highly recommend the science-based short fiction collections produced by the publisher.

Follow

Follow