When talking about of Battlestar Galactica, science, and religion, one will undoubtedly think of Ronald D. Moore’s re-imagined Battlestar Galactica (BSG) from 2003 rather than its predecessor, Glen A. Larson’s short-lived space opera of 1978. A sci-fi series that was not only uncharacteristically conservative for liberal Hollywood, but has also been regarded as one of the most impressive science fiction adaptations of religious teachings – specifically, Mormonism.

BSG has garnered frequent scholarly attention in the past decade, particularly in regards to the show’s gritty, realist portrayal of contemporary political challenges facing the United States, including, first and foremost, the threat of Islamic terrorism. In addition to its metaphorical portrayal of foreign policy issues – a frequent occurrence in science fiction television – the show, standing on such behemoth shoulders as Gene Roddenberry’s Star Trek and its engagement with the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, also did not shy away from controversial domestic policy debates. Set in an arguably much more desolate universe than Roddenberry’s Federation of Planets, BSG shines a critical spotlight on union and worker rights, election fraud, and areas where science and religion meet and clash, most notably stem cell research and abortion.

In fact, BSG’s stance on abortion is quite remarkable when read through a lens of the interconnection between science and religion: although she faces heated opposition from the scriptural literalist, fundamentalist – a somewhat overused term, though applicable in this case if one takes BSG’s prequel series Caprica into consideration – Gemenese population, humanity’s President Laura Roslin is firmly pro-choice. She is reluctant to outlaw abortion, despite the fleet’s dwindling numbers and thus the annihilation of her own race. In The Captain’s Hand Roslin struggles with the moral dilemma as she must decide if she will grant an abortion to a pregnant teenager. The cybernetic Cylons, meanwhile, go to extreme measures to achieve natural procreation, viewing it as a holy commandment from their ‘One True God’ and positioning themselves as staunchly pro-life, despite having previously annihilated almost an entire race of living beings.

BSG’s engagement with the abortion-debate in the United States covers merely a fraction of the show’s theological content, as Moore’s re-imagination developed its own intricate – and somewhat contested – religious story-arc that spanned four seasons. However, references to Mormonism are, according to its creators, purely of an homage nature to its predecessor.

Glen A Larson’s Galactica, meanwhile, is steeped not only in Mormon terms and phrases but also in its theology, unlike most popular culture representations of Mormon believers, which tend to focus on the – outlawed – practice of polygamy and rarely touch on actual teachings of the tradition.

The religious ingenuity of Larson, who was a practicing Mormon, lies in his careful interweaving of commonly known Biblical tropes and teachings with exclusively Mormon thought. This was a wise choice given the religion’s still somewhat tainted reputation across the United States and globally, as evidenced for example by the opposition former presidential candidate Mitt Romney encountered based on his Mormon beliefs.

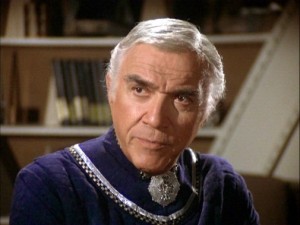

In his comprehensive book An Analytical Guide to Television’s Battlestar Galactica, John Kenneth Muir convincingly lists a plethora of religious elements in the series, most easily identified through the naming of characters. Commander Adama’s name originates from the the Biblical Adam, whose moniker not only means ‘man’ but also ‘Earth’ in Hebrew. This creates a classic nomen-est-omen effect as Adama, who doubles as military and religious authority for the Colonial fleet, leads his people towards Earth like Moses led the Hebrews towards the Holy Land (163-64). Lucifer is the only Cylon who actually has a name and, just like his famous namesake, is characterized through manipulation, deceit, and jealousy in the show (167). Commander Cain is a war hero who journeys through the heavens alone and enters into conflict with his ‘brother in arms’ Adama, similarly to the Biblical Cain and his status as a fugitive and lonely wanderer (170). (A parallel that, one might add, is enforced even clearer in Moore’s BSG, where Admiral Helena Cain kills her first officer and thus actually commits a kind of fratricide).

In addition to these general Christian tropes, Galactica includes specifically Mormon terminology such as describing a marriage as a ceremony of ‘sealing’, modeling as well as naming the Twelve Colonies’ government body after the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints’ ruling council Quorum of Twelve, or the inclusion and important role of the planet Kobol, an anagram of Kolob, the star “nearest unto the throne of God” (P of G, Book of Abraham 3:2) according to Mormon teachings (Wolfe 305-06).

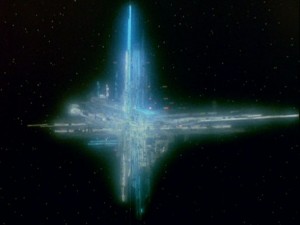

The show’s most striking – and, at the same time, completely unnoticeable to those whose knowledge of Mormonism does not go beyond polygamy, high birthrates, and no coffee or alcohol – inclusion of Mormon theology, however, is the storyline revolving around the ‘Seraphs’, a non-corporeal, technologically superior race that appeared in three episodes of the original show’s first and only season.

The humans first encounter the Seraphs, who are originally presented as translucent, angel-like beings who speak with disembodied voices, in the two-part episode “War of the Gods”. Following a deadly confrontation with the episode’s villain, a mysterious man named Count Iblis – whose dramatic reveal as a demon-like creatures strongly alludes to him being Satan himself – Apollo, the young, heroic son of Commander Adama, dies while protecting his comrades. In an unexpected turn of events Apollo, his best friend Starbuck, and the former’s love-interest Lieutenant Sheba are transported onto the Seraphs’ ship soon after, where the aliens resurrect Apollo, turning him into somewhat of a Jesus-metaphor given his status as the son of a religious authority figure, his martyr death and now miraculous return from the dead. Then, the mysterious beings inform a stunned and grateful Starbuck that, “As you now are, we once were; as we are now, you may become” (“War of the Gods: II”), which is a rewording of former Mormon President Lorenzo Snow’s famous quote: “As man is now, God once was; as God is now man may be.”

The belief that following the right teachings and living the correct practices during their time on Earth will lead to the ascension into a god-like existence after death is a central tenet of Mormon faith (Herrick 220-21). Larson’s decision to portray this god-like existence as a technologically superior, angel-like alien race is quite fascinating, given the often-cited divide between science and religion that informs many of the more conservative Christian traditions.

The ‘gods’ in Battlestar Galactica are clearly in favor of technological advances, which becomes even more evident in the later episode “Experiment in Terra”, where Apollo, the new god-in-training so to speak, is sent to the planet Terra to aid the inhabitants in ending their war against the evil Eastern Alliance (a less than subtle nod to the series’ contemporary context of the Cold War). He receives his instructions from a Seraph named John – allusions to John the Baptist may come to mind – who appears to him as a kind old man and continually offers advice.

Just as the president of Terra announces a peace treaty with the Eastern Alliance, the enemy launches a surprise attack, prompting Terra to retaliate and forcing Galactica to intercept the nuclear missiles racing towards each other. The series works with images that were clearly intended to strike fear in the hearts of a Cold War-weary nation. Additionally, as Battlestar Galactica is in itself rather conservative, the president’s naïve trust that peace can be achieved is not the show’s first criticism of contemporary foreign politics and Jimmy Carter, who was president at the time of Galactica’s original run and despised by the conservative, religious right.

Prompted by Terra’s president’s almost fatal declaration, Apollo, dressed in an angelic white version of his usual uniform, mounts the podium and proceeds to inform the Terrans that the opposite of war is not peace but slavery and that “strength alone can support freedom.” The fact that John ‘The Alien-Baptist’ approves of Apollo’s passionate plea for strength (read: re-armament) is perhaps somewhat contradictory of earlier scenes that seem to indicate the aliens’ overall distaste regarding violence. However, it is nevertheless striking that the ‘gods’ act as military commanders in this episode, leading Apollo onto the right path as he essentially tries to teach the lesser developed Terran civilization to put their faith in the military, not their civilian leaders. Before John whisks Apollo away to rejoin the Colonial fleet he forbids him from sharing any technological secrets with the Terrans, though it is strongly alluded to that they will one day reach the fleet’s level of technological sophistication, repeating the cycle of “As you now are, we once were; as we are now, you may become.”

The humans and Cylons in Moore’s BSG occasionally grapple with their faith, rebelling against the role the ‘One True God’ wants them to play. Larson’s Galactica, however, presents religious deities as clearly superior, wise, kind, and surprisingly helpful, while the humans follow their lead eagerly. This should not be all that surprising, given the fact that humans and ‘gods’ clearly share their belief in the superiority of technology and military strength. After all, as the humans are now, the gods once were.

Larson thus managed to create an intrinsically religious science fiction space opera, merging faith in a higher being with undying faith in the strength of science and technology and, by portraying the ‘gods’ as a superior alien race, finding a compromise that is actually quite remarkable, as it challenges the conservative stereotype of the incompatibility of science and religion by drawing its theological foundations from one of the more conservative Christian traditions – Mormonism.

Works Cited

Herrick, James A. Scientific Mythologies: How Science and Science Fiction Forge New Religious Beliefs. Downers Grove: InterVarsity, 2008. Print.

Muir, John Kenneth. An Analytical Guide to Television’s Battlestar Galactica. Jefferson: McFarland, 1999. Print.

Wolfe, Ivan. “Why Your Mormon Neighbor Knows More About This Show Than You Do.“ Battlestar Galactica and Philosophy: Mission Accomplished or Mission Frakked Up? Eds. Josef Steiff and Tristan D. Tamplin. Chicago: Open Court, 2008. 303-16. Print.

Stefanie Esser received her Bachelor of Arts in Political Science and Sociology from the University of Bonn (Germany) in 2009 and finished her Master of Arts in North American Studies in 2012 (also University of Bonn). She spent one year at the University of Kansas as a Fulbright scholar and is currently doing dissertation research at the Communication Arts department at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her areas of interest include Christian political fundamentalism, Christian fundamentalism in popular culture, and fan cultures.

Follow

Follow