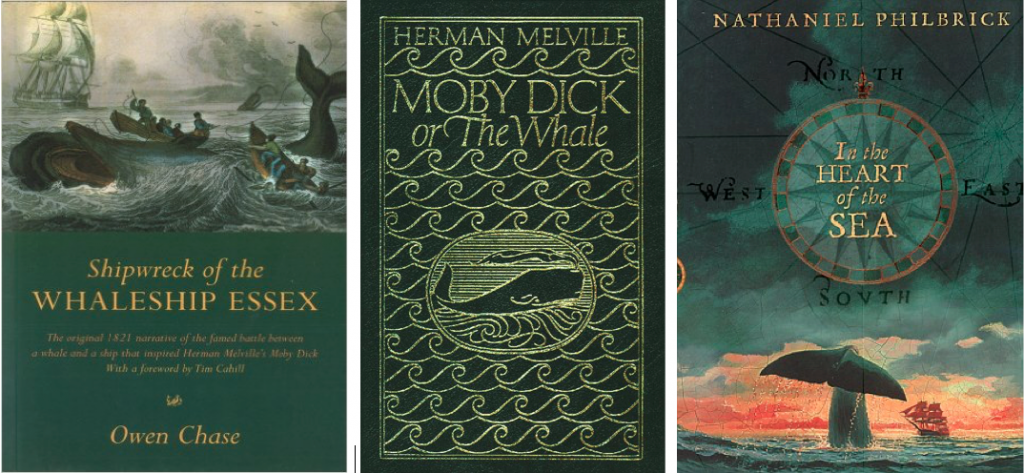

Will Ron Howard’s new film Moby Dick In the Heart of the Sea be Hollywood’s (and specifically Warner Bros.’s) final attempt to adapt Herman Melville’s epic novel Moby Dick? The film seems to act as proof that it can’t be done; at least not in a way that includes the deep themes, philosophical points, and science of the novel. This most recent attempt to bring the white whale to the silver screen is not technically based on Melville’s Moby Dick but instead on the 2005 historical-fiction In the Heart of the Sea by Nathaniel Philbrick. It’s an adaptation of a fictional account of the writing of Moby Dick that is based upon Owen Chase’s memoir Narrative of the Most Extraordinary and Distressing Shipwreck of the Whale-Ship Essex (1821) alongside an imagined history of Melville’s writing practices. Many film critics seem to have missed the complicated adaptation route even though they recognise it as a version of Moby Dick. So why are Warner Bros., who have now made four films about this vengeful giant sperm whale, returning to the story which has been a bit of a damp squid squib at the box office?

Firstly Ron Howard’s attempt to tame this mighty beast… a little myth busting is required from the outset here. Melville didn’t go to listen to a tale from a crewmember of the Essex; In the Heart of the Sea is not entirely based on true events even if it uses some historical sources. However, Melville did read Chase’s memoir of the Essex voyage as part of his research. The result is that at times the first act of In the Heart of the Sea, in fact the whole thing, feels to the well-read maritime history buff to be more based on Richard Dane’s novel Two Years Before the Mast (1840) – which is a maritime must-read. What I mean by this is that the narrative is more about life aboard a ship, and the story told to Melville in In the Heart of the Sea is told by a man who was a young greenhorn on the fateful voyage of the Essex. Therefore, from the outset the audience sees the story from the perspective of the crew, rather than just from amongst the officers. This young greenhorn, Thomas Nickleson (Tom Holland/Brendan Gleeson) replaces the part of Ishmael in Moby Dick, not by being the sole survivor of the Essex (as Ishmael is of the Pequod in Moby) but as the only remaining survivor. Ultimately the similarities of the plot and narrative of In the Heart of the Sea are too close to that of Moby Dick, which means that comparisons are inevitable and have even been made by the studios own promotional material. So this is Moby Dick.

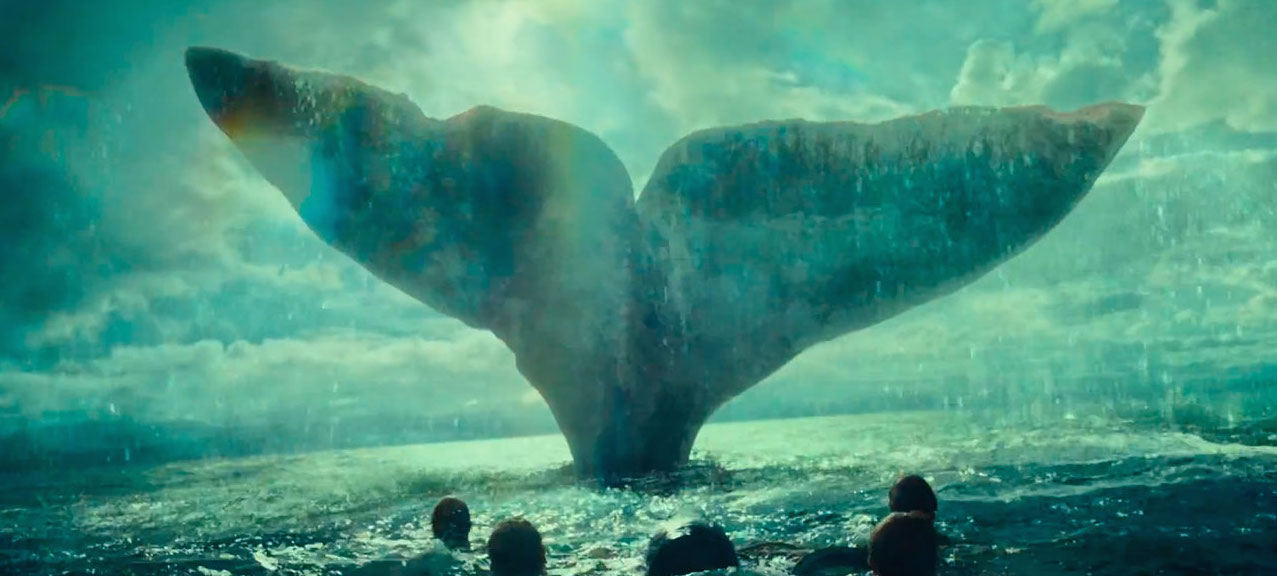

Herein lies the problem at the heart of the beast. Moby Dick is inherently unadaptable – it is one of the great American epic novels because of its diversity, and multiple literary layers and devices (songs, poems, asides, stage directions) exploring notions of class, status, and religion in the New World. Oh the story, the narrative, the action is the perfect Boy’s Own adventure, but as it’s shown in In the Heart of the Sea this really isn’t Melville’s story it’s Chase’s. Now, if In the Heart of the Sea was being put forward as an historical adventure thriller, independent of the poisoned Moby-Dick-chalice, then it is a fine movie – entertaining, rounded, horrifying at the right moments and challenging to audiences (and it’s not Star Wars for those sick of lightsabers and wookies). But it is impossible to separate In the Heart of the Sea from Melville’s Moby Dick. The whale looms large over the story, of not only In the Heart of the Sea but also over Warner Bros.’ previous attempts to adapt the epic.

Moby Dick has always been a bit of a flop. Herman Melville died believing his novel was a failure, pocketing only $1200 of earnings from the work. However, following the devastating destruction of the First World War Moby Dick saw a change in fortunes. Its bleakness spoke to a world recovering from loss and devastation more absolute and brutal than anything foretold in fiction. Re-printed as an Everyman’s Library edition in 1924, the novel was soon adapted for film, emerging as the silent film The Sea Beast (1926) directed by Millard Webb. John Barrymore was a contracted star with Warner Bros. and starred as the whaler, Capt. Ahab Ceeley, as part of a three-movie deal. The Sea Beast inauspiciously began a now ninety-year-old association with Moby Dick for Warner Bros., who made a second version in 1930 as a ‘talkie’ titled Moby Dick., which also features John Barrymore as Ahab. Both the 1926 and 1930 versions of the story were well-received by critics but these adaptations strayed dramatically from the novel; in The Sea Beast Ahab looses a leg to Moby Dick and gains a love interest in Esther Harper (Dolores Costello), and in 1930’s Moby Dick the romantic entanglements with Faith Mapple (Joan Bennett) are central to the narrative.

Moby Dick has always been a bit of a flop. Herman Melville died believing his novel was a failure, pocketing only $1200 of earnings from the work. However, following the devastating destruction of the First World War Moby Dick saw a change in fortunes. Its bleakness spoke to a world recovering from loss and devastation more absolute and brutal than anything foretold in fiction. Re-printed as an Everyman’s Library edition in 1924, the novel was soon adapted for film, emerging as the silent film The Sea Beast (1926) directed by Millard Webb. John Barrymore was a contracted star with Warner Bros. and starred as the whaler, Capt. Ahab Ceeley, as part of a three-movie deal. The Sea Beast inauspiciously began a now ninety-year-old association with Moby Dick for Warner Bros., who made a second version in 1930 as a ‘talkie’ titled Moby Dick., which also features John Barrymore as Ahab. Both the 1926 and 1930 versions of the story were well-received by critics but these adaptations strayed dramatically from the novel; in The Sea Beast Ahab looses a leg to Moby Dick and gains a love interest in Esther Harper (Dolores Costello), and in 1930’s Moby Dick the romantic entanglements with Faith Mapple (Joan Bennett) are central to the narrative.

The inaccuracies of these early adaptations frustrated director John Huston, who had wanted to make an ‘accurate’ adaptation for sometime when he approached Warner Bros. in the early 1950s. Ray Bradbury cheekily claimed that Huston was only interested in the project because he wanted to play Ahab himself but Bradbury agreed to write the screenplay for Moby Dick (1956), which remains the science fiction novelist’s only foray into script writing. Producing the film in England, Huston needed a whaling expert to advise him on the film and its representation of 18th century whaling practices. By the 1950s there was no longer a British whaling industry, and the world’s remaining whalers were generally confined to the Southern Ocean and Antarctic waters. The whaling described by Melville had all but disappeared and been replaced by factory whaling ships that harvested the oceans – a industrial development that in part inspired Arthur C. Clarke’s science fiction novel The Deep Range (1957). Fears that factory whaling would cause extinction of some species, due to its industrial efficientcy, led to the creation of the International Whaling Commission (IWC) in 1946 and ultimately to the moratorium on commercial whaling in 1982. Huston needed a science consultant who could give him an insight into a by-gone age of whaling – Robert Clarke of the newly formed National Institute of Oceanography (NIO) (credited at the beginning of the 1956 films as ‘The British Institute of Oceanography’) was that advisor.

The inaccuracies of these early adaptations frustrated director John Huston, who had wanted to make an ‘accurate’ adaptation for sometime when he approached Warner Bros. in the early 1950s. Ray Bradbury cheekily claimed that Huston was only interested in the project because he wanted to play Ahab himself but Bradbury agreed to write the screenplay for Moby Dick (1956), which remains the science fiction novelist’s only foray into script writing. Producing the film in England, Huston needed a whaling expert to advise him on the film and its representation of 18th century whaling practices. By the 1950s there was no longer a British whaling industry, and the world’s remaining whalers were generally confined to the Southern Ocean and Antarctic waters. The whaling described by Melville had all but disappeared and been replaced by factory whaling ships that harvested the oceans – a industrial development that in part inspired Arthur C. Clarke’s science fiction novel The Deep Range (1957). Fears that factory whaling would cause extinction of some species, due to its industrial efficientcy, led to the creation of the International Whaling Commission (IWC) in 1946 and ultimately to the moratorium on commercial whaling in 1982. Huston needed a science consultant who could give him an insight into a by-gone age of whaling – Robert Clarke of the newly formed National Institute of Oceanography (NIO) (credited at the beginning of the 1956 films as ‘The British Institute of Oceanography’) was that advisor.

Robert Clarke read Natural Sciences at the University of Oxford, and following graduation he was sent out as a whaling inspector on the British factory whaler Southern Harvester for 1947/8 season (Second Inspector on the the British whale factory ship Southern Harvester for the Antarctic season 1947/1948). Following this baptism of fire, Clarke was appointed to the newly founded NIO in 1949. His first research publication, ‘Open boat whaling in the Azores: the history and present methods of a relic industry’ (Discovery Reports 26, 1954), observed traditional whaling practices in the Archipelago of the Azores (now the Autonomous Region of the Azores), where whaling was still conducted from long boats with thrown harpoons. This article was probably the work that brought him to the attention of Huston. This work also reflected a shift in British marine biological studies of Cetaceans which was moving away from destructive research practices tied to the whaling industry towards other more statistical studies of whale populations. Clarke’s work in the Azores, whilst essentially anthropological in nature, was actually intended to discover the best way for attaching a mark to a whale so that their movements could be tracked by oceanographers.

Robert Clarke was an absolute Melville/Moby Dick fanatic as well as an expert on the history of whaling. In a letter to Huston (28 April 1954) he wrote ‘the night you left for Ireland [from London], Ray Bradbury and I spent many hours discussing the script of MOBY DICK.” How Bradbury felt about his creative work being critiqued by a scientist isn’t recorded, but Clarke was certainly critical but later informed Huston that he thought the script “very fine indeed.” Except the ending which he felt was ‘sentimental and a betrayal of the fateful and supernatural power which the film gathers as the voyage proceeds.’ Clarke also wrote a long multi-page letter to Huston (4/5/1954) full of suggestions and amendments to the script, finally suggesting that he and Huston should go through the whole script together. Clarke was very invested in the project; he wanted to be a collaborator focused on historical and scientific accuracy rather than simply a technical advisor. For their part, Huston and Bradbury couldn’t rid themselves of Clarke.

In June of 1954 Huston sent film units to the Azores to capture footage of the locals carrying out whaling expeditions. Clarke provided not only unpublished catch statistics, but also contacts with local whalers and suggested where and when to go. Eventually unable to stay away Clarke travelled to the Azores to assist the film unit in person (whether he they wanted him to or not…). These shots were very important and they are used throughout the film: the mid to long shots in the whale hunt sequences are of actual hunts captured in the summer of 1954. This sojourn to the North Atlantic was also useful for Clarke, who had led a disastrous round-the-world expedition for the NIO between 1951-2, which had spectacularly ended in a military court-martial. Clarke and the ships officers had drunkenly gatecrashed a party hosted by the wife of the Admiral of the Simon’s Town Naval base in South Africa. These drunken antics nearly led to the cutting off of funding to the oceanographers by the Royal Navy! The issue was only resolved when the director of the NIO (George Deacon) agreed that Clarke would never be allowed to lead or command a British Oceanographic expedition ever again. Working on Moby Dick was a welcome distraction from this personal and political disaster.

Alongside archival footage of whaling, Huston’s Moby Dick needed some serious props: specifically the whale and the Pequod (the whaling ship described in Melville’s novel). Without the advantages of modern CGI, Huston and his artistic director Ralph Brinton needed a real ship, however wooden vessels from the 1850s were rare with many having been lost to rot, neglect, or decay. The ship they eventually settled on for the Pequod was the Hispanola, built in 1879 and already converted by Walt Disney for movie-use in Treasure Island (1950). It was less a historic ship and more a movie prop, having been extensively remodeled to improve camera access. Disney had sold the ship to Scarborough Council who weren’t really sure what to do with her and they were happy to sell on to Huston and Warner Bros.

The white whale has a far more complicated story. Although real footage reduced the amount of artificial studio shots required, the peculiar movements of Moby Dick necessitated the construction of a model whale. Brinton was convinced that the only way to achieve this was by contracting the assistance of experts in submarine technology. The major problem with this was that submarine technologies were quickly becoming one of the most secretive of the Cold War sciences. Despite the British Royal Navy officially refusing to ever discuss submarine operations, Brinton wrote directly to armaments manufacturer Vickers-Armstrong: ‘I wonder if you could help us in the following matter… we need a big whale model.’ The Admiralty were asked to provide midget submarines, famously used in a failed mission to blow up Battleship Tirpitz in 1943, but refused claiming that they were worn out and new ones hadn’t been delivered. This is a highly dubious claim seeing as the ‘worn out subs’ were used in the feature film Above Us the Waves (1955). So submarines dressed as whales never happened because propaganda came before entertainment.

The first secretary of the Royal Navy Sir John Lang felt that the challenge of creating Moby might be a useful development exercise in light of the need for improved submarine technologies. He explained that ‘on the construction of the leviathan itself my constructional people are cautious’ as they as had been trained in the construction of solid vessels, not ones that articulated their movements like a fish. Nevertheless, Lang wanted to offer some sort of assistance to the film project, and therefore he put forward some information he had been given by the Joint Services Organisation. He omitted this group’s true title and instead described them as a group that dealt ‘among other things, with camouflage and deception’. A Southend-On-Sea based company Lea Bridge Industries were also employed as part of this props projects to make the whales skin/blubber, they were described as specialising in ‘plastics and rubber production of an unusual nature’. The receipt of this letter caused Moby Dick’s producer Eliot Hyman to quip: ‘it would be amusing if the consequence of the building of the whale with the help of the British Admiralty would, as it very well might, result in an extraneous benefit to them as a result of their perhaps envisaging a new type of equipment for submarine warfare. This could happen.’ It is unknown as to whether the Admiralty benefitted with their flirtation with Hollywood (but it’s unlikely) and they certainly weren’t given a screen credit.

Scientists were central to the story of Huston’s Moby Dick. They advised on gathering real footage and techniques (rather ferociously in the case of Robert Clarke) and facilitated the creation of an articulated whale model. But even with with today’s modern CGI making Moby Dick or a derivative of it seems remain a whale of a challenge for filmmakers. Beyond the technical aspects of producing such a film, communicating the sea as a frontier, with its complex superstitions, harsh lessons, and frustrating reliance on tough masculinities, appears far more difficult than making a new Star Wars. In the Heart of the Sea is a good adventure movie, thankfully an alternative to Star Wars mania this Christmas, but it is not going to uproot Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World (dir. Peter Weir, 2003) as the epic historical sea adventure of the 21st century. Moby Dick remains an elusive beast for filmmakers: are its deeper philosophical themes unattainable by entertainment media, or are they just so outdated that it’s time for Moby Dick to be sent to Davy Jones’ (movie) Locker?

Dr Sam A. Robinson is a research associate on the Unsettling Scientific Stories project at the University of York. Sam researches the history of oceanography, science and the state, Cold War science diplomacy, and science fictions/futures.

Research conducted at the AMPAS Margaret Herrick Library (Los Angeles) revealed the story of the British Admiralty’s involvement in the creation of the mechanical whale for the 1956 Moby Dick movie. Correspondence can be found in special collections within the ‘John Huston Papers’.

Follow

Follow