Do vampire narratives become science fiction when vampirism is created or/and ‘cured’ by science? Whether benevolent, malicious, or uncontrolled, science is rivalling if not, in some cases, entirely replacing the supernatural as the most prevalent component of recent vampire narratives. Where once there was a vampire slayer and her pointy stick there are now scientists armed with vaccines and syringes.

This post was inspired, in part, by the delightfully trashy Netflix original horror series Hemlock Grove because of the incorporation and development of a science-based narrative in the most recent season. It should be noted that the ‘science’ in Hemlock Grove is problematic (to say the least) but I do not want to get into a discussion of scientific accuracy but instead consider how and where science is used in this, and other recent scientific/supernatural stories. While the series’ critical reaction has been poor it has developed a strong fanbase with a young active online community that has helped to secure the show’s third and final season. The first two seasons of Hemlock Grove introduce the strange world of fabulously wealthy heir Roman Godfrey (Bill Skarsgård) and his mother Olivia (Famke Janssen) who are the CEOs of the Godfrey Institute for Biomedical Technologies in the small town of Hemlock Grove. Roman and his mother are revealed to be upir (a vampire of Eastern European descent). Roman shares a psychic link with a newcomer to the town, Peter Rumancek (Landon Liboiron), a Romani gypsy werewolf (obviously). Peter and Roman share prophetic dreams that foretell mysterious brutal murders and they must work together to save the victims and conceal their own dangerous secrets and identities.

At its core Hemlock Grove is supernatural; upirism and lycanthropy are not viral or the result of scientific blunder, but inherited. Alongside the often overly chaotic supernatural narratives the series is concerned with issues surrounding bioscience, eugenics, and medical ethics. The town’s main employers, following the collapse of the steel industry, are two medical institutions: the Hemlock Acres Hospital and the Godfrey Institute for Biomedical Technologies (whose experimental biomedical research wing is referred to as the White Tower). During the second season, released on Netflix during the summer of 2014, the use and abuse of science becomes a far more pronounced theme. The magic realism, fantasy, and perplexing aesthetics of the first series are replaced or rather suppressed by questionable science. The development of secondary character Dr Johann Pryce (Joel de la Fuente), the Godfrey Institute’s brilliant but mad ruthless lead scientist, underpins this change in tone. Pryce is an unrestricted research scientist who believes and seemingly has the capacity to create life from death.

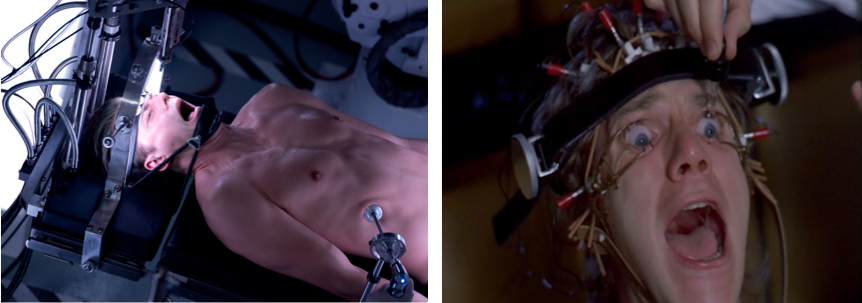

Pryce grows a female humanoid in his lab (Project Ouroboros/Prycilla [Alexandra Gordon]); uses off-cuts and failed flesh experiments to slake Olivia and Roman’s vampiric blood lust; and in scenes reminiscent of A Clockwork Orange’s Ludovico Technique begins ‘curing’ Roman of his upirism with shock therapy and syringes thrust into his eyeballs. Olivia sees her upirism as a blessing whereas for Roman it is a curse that Pryce is sure he can eradicate via a gruelling series of treatments. During these torturous sessions Roman cannot be anaesthetised and Pryce just tells him to ‘think happy thoughts’ – a response that is deliciously evocative of many a Kubrickian sociopath. Pryce attempts to improve upon humanity with lab-made organs, and bodies that can be imprinted with the personalities of deformed or physically disabled people (he gives up scientific accolades to ‘help’ Shelley [Madeleine Martin] – Roman’s curiously deformed sister – by transferring her consciousness to humanoid Prycilla’s). Pryce promotes the reproduction and adaptation of people with desirable or unique traits (positive eugenics) and attempts to alter or replace those that do not fit his (still unclear) vision. According to Pryce, the supernatural is a biological trait, a scientific subversion that can be bred out, swapped out, or violently ripped out.

Hemlock Grove is recent example of entertainment media that incorporates medical narrative alongside or instead of a supernatural one. Other interesting examples include the most recent incarnation of I am Legend released in 2007. This third filmic outing of the narrative, following The Last Man on Earth (1964) starring Vincent Price and the Charlton Heston vehicle The Omega Man (1971), is an adaptation of the previous films as well as Richard Matheson’s 1954 novel also titled I am Legend. Neville, the lead character, is presented as the sole survivor of airborne virus that wipes out the majority of humanity and leaves behind a mutated race of vampires. In the Heston version the ‘Family’ is the result of germ-warfare between China and Russia, and they are not clearly defined as vampire in a move away from Matheson’s source novel that fits in with the 1970s (Cold War) post-apocalyptic disaster cinematic turn. Will Smith’s Neville is a virologist and the creation of a bestial vampire-like species is the result of a lab-created virus that was originally intended to cure to cancer. Neville, the scientist, saves the future of humanity with his blood. He sacrifices himself as his blood is a natural cure to an unnatural virus.

A further example of the influence of science on vampire narratives can be found in Daybreakers (2009) in which traditional vampire superstition is replaced with post-apocalyptic science fiction. A plague (laughably caused by an infected vampire bat) transforms part of human population into vampires. The human population shrinks as the need for blood increases and a vampire corporation farms human blood while also working on a blood substitute. It is the extension of the vampire myth within a scientific frame with other examples including Blade (1998), and Ultraviolet (2006). Without fresh human blood the virulent vampires of Daybreakers deteriorate mentally and physically into mindless monsters. The cure that is accidentally developed returns vampires back to their original human state. By ‘saving’ the immortals from vampirism they become mortal and as one character exclaims ‘Welcome back to humanity. Now you get to die.’ Once treated the cured person can heal others; their blood becomes the antidote and if they are fed upon they will pass on the cure. Science triumphs over the disease of vampirsim. Similarly, in earlier film’s such as Kathryn Bigelow’s Near Dark (1987) science prevails over vampirism through the use of blood transfusions. Unusually, for a 1980s film, references to the AIDS epidemic are surpassed by the celebration of blood ties and the use of blood to rejoin and reinforce the family.

The popular, but again trashy series, True Blood explained away many vampire myths as superstitions created by vampires to protect themselves before they came ‘out of the coffin’, Vampire Bill Compton (Stephen Moyer) holds a history lecture in a church and even holds a cross to prove that he is not a monster. He presents himself a God-fearing Southerner who is also a vampire. The vampires in that series are able to attempt integration into human society once Japanese scientists develop a sustainable substitute to human blood called Tru Blood. This lab-created synthetic alternative is a core element of the series that gives the world’s large vampire population the nourishment they need to survive without the need for human blood. In the final season of the series the supply of True Blood is contaminated by a lab-created AIDS-like virus (called Hep-V) that slowly and painfully kills the vampires. Scientists are presented as both positive and negative forces for the successful merging of the human and non-human worlds. In the conclusion of the series an antidote to Hep-V is discovered in the blood of one of characters and synthesised into a blood substitute called New Blood. It is created by the same bench-scientist who produced the original product – the heroic scientist eventually saves the day the but only after the restricting corporations and governments allowed them to. True Blood combines some of the traditional aspects of the vampire myth with contemporary science-based elements that draw upon current issues surrounding the impact, restriction, and politics of scientific research.

The myth of the vampire has pathological origins, as Katherine Byrne (2011:124) explains in Tuberculosis and the Victorian Literary Imagination:

“The history of the vampire myth is, of course, in essence the history of disease itself, for the belief in the Undead rose out of a need to explain mysterious or untimely death in past cultures which has little medical understanding and therefore associated illness with supernatural forces.”

Medical science has advanced astronomically since the inception of the vampire myths, and it is perhaps unsurprising that as the expectations and achievements of scientists advance so do the fictional representations of these historical bloodsuckers. Media producers have adjusted their own narratives to frame vampires within science fiction rather than supernatural gothic horror. Although cures and human enhancements often lead to post-apocalyptic futures in these films, scientists are at least initially employed within the narrative to improve human lives. The need for supernatural explanation no longer exists for many people; there are still medical mysteries but not necessarily a need for explanations beyond science.

Follow

Follow