We are experiencing a golden age for the fusion of science and entertainment. Oscar-winning films such as Gravity and The Theory of Everything, television ratings titans like The Big Bang Theory, and high-traffic web-comics like XKCD have shown that science-based entertainment products can be both critically and financially successful.

Many scientists are concerned about how this blending of science and entertainment might affect public perceptions of science. Such concerns are legitimate—there is a significant amount of research showing that entertainment products do have a powerful influence on public attitudes towards science.

The most constructive way to deal with these issues is to engage with entertainment producers. In the US, several high-profile scientific organizations have developed initiatives that help researchers to participate as science consultants to the entertainment industry. These include the National Academy of Sciences’ Science and Entertainment Exchange, the University of Southern California’s Hollywood Health and Society programme, and the multi-sponsored Entertainment Industries Council. All work to connect entertainment industry professionals with top scientists and engineers.

These initiatives have led to scientists’ involvement in projects as diverse as the television series Breaking Bad and the first-person-shooter video game The Last of Us (Scientific American did a great post on the game’s plausible zombies). Indeed, it would be surprising today if a US-produced film, TV or computer game containing substantial scientific content did not have a science consultant on board.

Our research group, the Science and Entertainment Laboratory, along with the science fiction writer Geoff Ryman, are in the process of developing a UK equivalent, the British Art and Science Exchange. Similar to the service currently provided by the Science Media Centre for news journalists, BASE would be a clearing-house for scientists willing to advise the UK entertainment industry.

While it has a smaller film industry than the US, the UK has other major strengths in the creative arts such as thriving theatres, world-class publishers, respected broadcasters, a fertile music industry and an underappreciated computer game industry.

Unlike in the US, though, the UK’s cultural climate is less hospitable towards such an initiative. British learned societies and science advocacy organizations have been more conservative in their approaches to communicating science through entertainment. Some British scientists are also been wary of embracing entertainment as a vehicle for science communication.

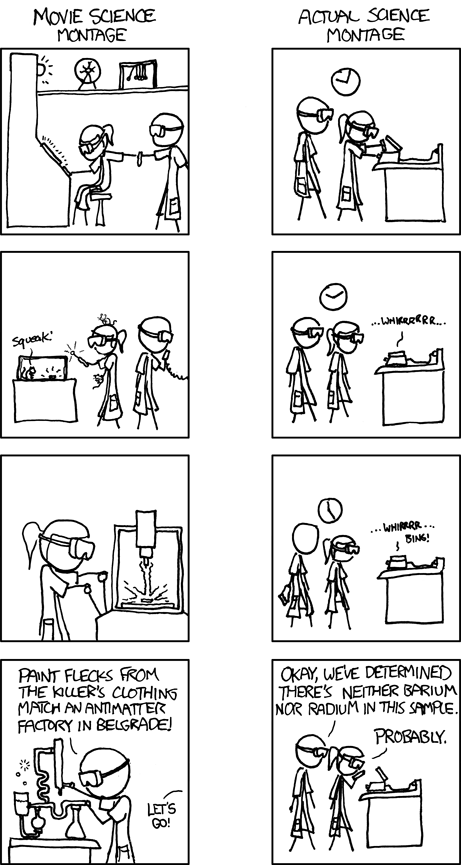

Part of this reluctance stems from a misunderstanding that conflates communication with education. Entertainment products are certainly not ideal vehicles for teaching scientific facts, but high-profile entertainment narratives have an unmatched capacity to convey the excitement and promise of research. This is particularly true if we move beyond simplistic notions of science as a collection of facts in a textbook and, instead, consider it as a larger social institution that embodies the systems of science—including methods, interactions among scientists, and a broad cultural context in which science is conceived and practiced.

Part of this reluctance stems from a misunderstanding that conflates communication with education. Entertainment products are certainly not ideal vehicles for teaching scientific facts, but high-profile entertainment narratives have an unmatched capacity to convey the excitement and promise of research. This is particularly true if we move beyond simplistic notions of science as a collection of facts in a textbook and, instead, consider it as a larger social institution that embodies the systems of science—including methods, interactions among scientists, and a broad cultural context in which science is conceived and practiced.

Scientists and organizations that advise entertainment professionals have an unprecedented opportunity to influence depictions of scientific knowledge, scientists, and scientific institutions in powerful storytelling media. NASA helped the makers of Gravity and Interstellar not to teach science to the public, but to shape the agency’s public identity.

Entertainment products have also proven extremely effective at raising awareness and convincing the public that a scientific issue needs more political, financial, and intellectual attention. For example, Columbia University microbiologist Ian Lipkin worked on Contagion because he believed that the film had the power to raise attention to the threat of emerging viruses.

For these collaborations to be effective scientists must recognize the cultural differences between entertainment and science. Scientific cultures are generally egalitarian academic communities, but entertainment productions tend to be hierarchical, with a rigid system of superiors and subordinates. Likewise, straightforwardness may be accepted or valued in science, but entertainment professionals seldom appreciate being bluntly told that their scripts are scientific nonsense.

For these collaborations to be effective scientists must recognize the cultural differences between entertainment and science. Scientific cultures are generally egalitarian academic communities, but entertainment productions tend to be hierarchical, with a rigid system of superiors and subordinates. Likewise, straightforwardness may be accepted or valued in science, but entertainment professionals seldom appreciate being bluntly told that their scripts are scientific nonsense.

Most importantly, scientists need to remember that just as they are experts in their field, the same goes for entertainment professionals. This means that scientists need to respect how entertainment professionals use their own creative expertise in dealing with the constraints imposed by their particular medium when they incorporate science.

Ultimately, we believe that the use of entertainment for science communication is good for both the entertainment industry and the scientific community. Scientists can help entertainment professionals use authentic science to make their texts more dramatic, interesting, and enjoyable. And the stories told about science in entertainment products can communicate a sense of awe about the natural world and our ability to understand it.

This post was originally commissed by Research Fortnight – ‘the only UK publication that connects research to funding and policymaking’. It was published as an article in both their print and online editions.

Follow

Follow

Hello,

It is amazing to hear that there are more initiatives to connect scientists to creative arts, also, in UK and Europe. Did you hear about SC4LA -scientific consulting for literature and art- (www.sc4la.com)? As a, currently, UK based scientist and science writer; I have founded this web-platform last year, when I was living in the continent. It is developing, although slowly, with a journal alongside; that aims to mention about current science in media and literature. I would be very happy to discuss about it with you. If you would like, you can contact me through contact@sc4la.com or my personal e-mail address. Best…