This post originally appeared on Physics Today.

I study and write about movie science for a living. As such, family, friends and colleagues constantly ask me if I hate movies with “bad” science. To which I always answer: No! I hate bad movies regardless of whether the science is “good” or not!

My book Lab Coats in Hollywood explores how filmmakers have utilized scientists as consultants in the present and in the past. One of the things I learned in writing this book is that we as a society get way too bogged down in the idea of “accuracy” when we judge movie science. For one, accuracy is a problematic term when we are talking about things that are inherently fictional. I much prefer the terms authenticity and plausibility, which can capture how closely we think a movie’s science represents real world science without being bogged down with unrealistic expectations that come with holding movie science to the lens of “accuracy.” Second, and more importantly, the true measure of a fictional film’s science should not be how accurate it is but should instead be on how effectively it uses that science to tell a unique and exciting story.

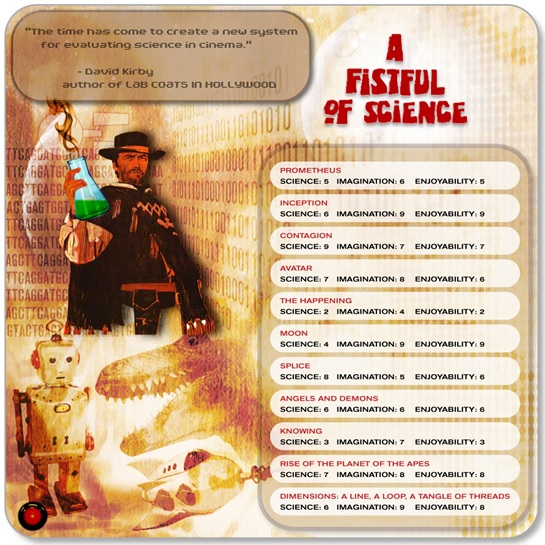

The release of an intriguing indie science fiction film called Dimensions got me thinking more about how, and why, filmmakers use science in fictional films. What’s more it got me thinking about how we as a society currently evaluate the science in movies. Dimensions is a time travel romance whose main character is a scientist. If I were to rate the authenticity of the science in the film I might give it a 6 on a scale of 1 to 10. Not great, but not bad.

But, judging this film’s science solely on this criterion would be missing entirely the point of what the film does with its science, which was far more innovative than many big budget blockbusters whose science may be more “accurate.” The film uses scientific theories about dimensionality to develop an engaging narrative and to explore universal human themes regarding how the past shapes our identities, our relationship to other people, and our conceptions of fate. Judging Dimensions on its imaginative use of science to tell an interesting storyI would give it a 9 out of 10. Plus, it was a thoroughly enjoyable film, which is another way we should be thinking about when we judge movie science.

I think the time has come to create a new system for evaluating science in cinema. A system that would not merely judge a film’s scientific authenticity on a scale from “good science” to “bad science,” but one which would also determine if the science was being used in novel and imaginative ways, as in Dimensions. We could hold the film to the same scale we would for any film regardless of how authentic the science is: Is it enjoyable? I applied this new system to ten high profile films from the last five years.

Prometheus

Scientific Authenticity: 5/10. Some of the astronomy in the movie is (relatively) authentic, like the alien moon, but much of the science is inauthentic at best (calling 35 light years distance as “a half billion miles from earth”) and ridiculous at worst (claiming a 100% DNA match between the “engineers” and humans). The unprofessional scientist characters tip this film into the realm of the scientifically ludicrous including the archeologists treating artifacts like the are collecting sea shells, the geologist who gets lost, and the biologist who approaches an unknown alien species as if he is trying to coax a cat from under the couch.

Imaginative Use of Science: 6/10. Although the theme is not uncommon in science fiction cinema (see 2001: A Space Odyssey), the idea of aliens directing human evolution is an intriguing use of science in the film. Unfortunately, any thought-provoking questions about the origins of humanity raised by this theme are undercut by the intelligent design inspired gibberish spouted by the main scientist character.

Enjoyable Film: 5/10. Despite some potentially interesting uses of science, the film’s idiotic scientists and implausible science ruin its entertainment value.

Inception

Scientific Authenticity: 6/10. Given the fantastical nature of the film’s dream invasion plot, some of the science is surprisingly authentic. Recent neurological studies have shown that it is possible to read minds and to record dreams. But, the brain’s complexity and our limited understanding of how thought patterns form make the ability to plant a higher-order thought in a person’s brain pretty far-fetched.

Imaginative Use of Science: 9/10. The science provides the foundation for a visually stunning crime thriller set in a dream within a dream within a dream. The science allows the filmmakers to explore fascinating philosophical issues concerning the nature of the subconscious, the distinction between dreams and reality and the conception of movies as a shared form of dreaming.

Enjoyable Film: 9/10. The science helps the film succeed on multiple levels: as a visual triumph, as a first class psychological thriller and as a character study.

Contagion

Scientific Authenticity: 9/10. The assistance of real-life scientists paid off for this film. Almost every scientific element in this film feels authentic. The laboratories, the scientists, the source of the virus, the disease’s epidemiology and the response of the CDC all ring true. The speed in which they develop a vaccine is a bit too quick, but overall the film is a scientific winner.

Imaginative Use of Science: 7/10. The most intriguing use of science was the film’s exploration of how our society would realistically respond to such a deadly epidemic. The film also delves into the internet’s murky role in disseminating both legitimate and illegitimate health information. However, some of the drama emerging from the film’s science is uninspiring such as subplots about the head of the CDC misusing insider information and about the distribution of vaccines in poor countries.

Enjoyable Film: 7/10. The authentic science leads to a documentary feel for much of the film. But, the need for drama conflicts with this pseudo-documentary approach and the film suffers from a genre split personality disorder trying to be a science thriller, an apocalyptic film and a political drama all at the same time.

Avatar

Scientific Authenticity: 7/10. The ecological aspects of Pandora’s flora are based on extensive botanical research and ideas from exobiology. The idea of using a brain-computer interface to control another body is becoming more plausible, even if the notion of creating an alien/human DNA hybrid is a bit fanciful. The scientific authenticity of Pandora as a self sustaining organism depends on how receptive you are to the Gaia hypothesis.

Imaginative Use of Science: 8/10. The film uses its science to create a visually rich world that was particularly impressive in 3D. Transferring the hero’s consciousness into another biological body is also a novel way to explore the theme of a white man experiencing life within a minority group. The Gaia hypothesis is also well deployed to support the film’s overt eco-message.

Enjoyable Film: 6/10. Despite its authentic and imaginative science, the film is Exhibit A for why good science is never enough to overcome the unoriginal storytelling. (Although the film would score 7/10 if watched in its original 3D.)

The Happening

Scientific Authenticity: 2/10. The film is correct to state that many plant species have chemical defenses, but this point is completely undercut by the laughable science in the rest of the film. Any film where a science teacher posits that scientific investigation is limited because there are “forces that work beyond our understanding” is scientifically indefensible.

Imaginative Use of Science: 4/10. While the “plants killed everyone” plot was widely panned by critics, it is actually an intriguing idea for a science fiction horror film that harkens back to the eco-horror films of the early 1970s. But, the potential to make an imaginative film based on plant’s chemical defenses rests on how well the filmmakers use the science. These filmmakers did not do such a good job with the science.

Enjoyable Film: 2/10. The flaws in logic and misuses of a potentially interesting scientific idea (along with some pretty terrible acting) render this almost unwatchable. The intelligent design inspired dialogue even prevents the film from becoming an MST3K style bad film guilty pleasure.

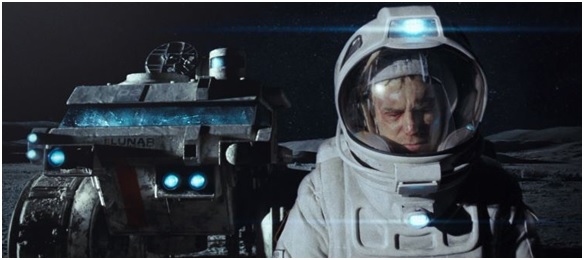

Moon

Scientific Authenticity: 4/10. Very good (if somewhat flawed) depictions of space exploration and the possibility of mining for minerals on the Moon. But the film’s (mostly unexplained) cloning scenario is highly implausible since it relies on adult clones with implanted memories.

Imaginative Use of Science: 9/10. The science may not be authentic, but the filmmakers are more interested in using the science to explore some fascinating ethical and philosophical issues associated with space colonization, human cloning, and the commercialization of engineered organisms as well as about identity and memory.

Enjoyable Film: 9/10. This is a thought provoking film whose cloning scenario, while implausible, allows for some excellent acting and for some great psychological drama.

Splice

Scientific Authenticity: 8/10. Splice hits the nail on the head in terms of its laboratory scenes and its use of scientific terminology. And while the idea of creating a fully developed human/animal hybrid currently seems impossible, genetic engineering is a powerful scientific tool that has already been used to create a new synthetic life form and human-animal genetic hybrids are now common.

Imaginative Use of Science: 5/10. The film spends a good deal of time on the interesting issue of corporate science in the 21st century. It also gestures towards an intriguing story about the ethics of manipulating human DNA and scientists’ responsibilities towards genetically engineered creatures. But, the film wastes its potential by essentially re-hashing Frankenstein and the old chestnut about not “playing God” with a strange pseudo-incestuous sex scene between one of the scientists and his creation thrown in.

Enjoyable Film: 6/10. Like the genetically engineered Dren, the film is a failed hybrid that professes to take on significant moral issues with science but which ultimately devolves into a standard monster move.

Angels and Demons

Scientific Authenticity: 6/10. Assistance from CERN’s scientists delivered authenticity in the dialogue and sets for the scenes set at CERN. Antimatter exists and it will create pure energy when it comes into contact with matter, which makes the science behind the plot credible. But, it would take over a billion years with current technology to make the amount of antimatter described in the movie, which makes the plot highly implausible.

Imaginative Use of Science: 6/10. The choice to use particle physics as the hinge for a plot focusing on a science/religion debate is novel since these debates frequently center on issues in biology. Antimatter’s presence at the birth of the universe makes it an interesting symbol for discussions over “creation.” Particle physics also provides an opportunity for characters to discuss the “God particle.” In the end, though, the film fails to follow through on the potential of its science vs. religion theme by settling for the easy “can’t we all get along” conclusion.

Enjoyable Film: 6/10. Unfortunately, the thriller elements in this film are not very thrilling (just what every action film needs: a trip to the archives!). The mishandled science/religion theme also renders this film a mediocrity.

Knowing

Scientific Authenticity: 3/10. Nicholas Cage’s does a surprisingly credible job as a university astrophysicist in his early scenes. The film also includes a pretty good summary of the Drake equation that is used to estimate the number of potential alien civilizations. But, the film’s dependence on numerology as a “science” threatens any claims to scientific authenticity the filmmakers might have had.

Imaginative Use of Science: 7/10. Like Angels and Demons, the film uses its science to engage with debates over science vs. religion. Unlike Angels and Demons, however, this film seriously engages with this issue. Randomness (science) versus determinism (faith) supplies a major theme within the film.

Enjoyable Film: 4/10. This film shows how a movie can use its science in an imaginative fashion, but still fail to be entertaining when these ideas are not well executed. The films’ numerous flaws in logic also take away from its entertainment value.

Rise of the Planet of the Apes

Scientific Authenticity: 7/10. The laboratory sets and much of the scientific dialogue were authentic as is now routinely the case for major Hollywood films. Gene therapy using viral vectors is being studied as a potential treatment for Alzheimer’s disease as shown in the film. Although the idea that Caesar ultimately learns to speak is problematic because chimpanzees lack the anatomical structures for speech.

Imaginative Use of Science: 8/10. The film’s use of genetic engineering in the creation of a “monster” is not a forced plot point as is the case with many horror films. The film asks us to understand that the scientist is conducting these experiments because he sees the disease’s impact on his father. The film’s science is also not used in the service of a lame anti-science rant. Instead, the film’s science provides the foundation for a commentary on the fate of captive animals (the humans in the sanctuary are far more cruel to the apes than any of the scientists were).

Enjoyable Film: 8/10. This film is one of the few science fiction films to include enough satisfying action scenes while also engaging with sophisticated scientific and ethical issues.

Follow

Follow