A while ago I found a journal article entitled Neural Decoding of Visual Imagery During Sleep. Intrigued by the title, I took a closer look and learned how a team of neuroscientists led by Yukiyasu Kamitani, based at a research lab in Kyoto, used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) technology, more commonly referred as a ‘brain scanner’, to record human brain activity during sleep. Nothing new here, except that the brain activity of healthy subjects was recorded during their dreams and, here’s the fascinating part, the pattern of activity was subsequently decoded to produce images and words that closely matched the perceptual experiences and verbal description obtained from participants on awakening from their dream.

Whilst the article and supplementary material explained the experimental procedure, technology, and mathematical model used to convert recordings of brain activity into pictures and words, I was transfixed and a little unsettled on viewing a short accompanying movie Dream decoding from human brain. The movie is just over one minute in length and consists of a rapid sequence of images and words that fluctuate in size according to computer analysis of recordings of brain activity during dreams.

The researchers point out that the movie is not meant to depict the shape or colour of dreams as perceived by those who took part in the experiment. Instead, it’s supposed to indicate the kind of objects, scenes, and semantic categories (visual and verbal) likely to be present in their dreams or the kind of images that would produce similar brain activity in the visual cortex. Nevertheless, the flurry of images and undulating words in the dream movie look remarkably similar to the verbal reports provided by two subjects on awakening. Spooky, don’t you think?

Attempts to record dreams and reproduce or simulate them in the form of pictures and sounds is a theme that has been explored by science fiction authors and filmmakers as well as scientists. Indeed, filmmakers have routinely consulted scientists and technicians for advice on how to depict dreams on screen. Before moving on to examine how two film directors collaborated with other artists, craftspeople, technicians, and scientists to portray dreams in mainstream films, I’d like to briefly mention another scientific experiment on mapping human brain activity to visual displays and experiences. This experiment is relevant here because it involved using short films referred to as ‘natural movies’ as stimuli during experiments and the results and methods can be applied to reconstruct dream images.

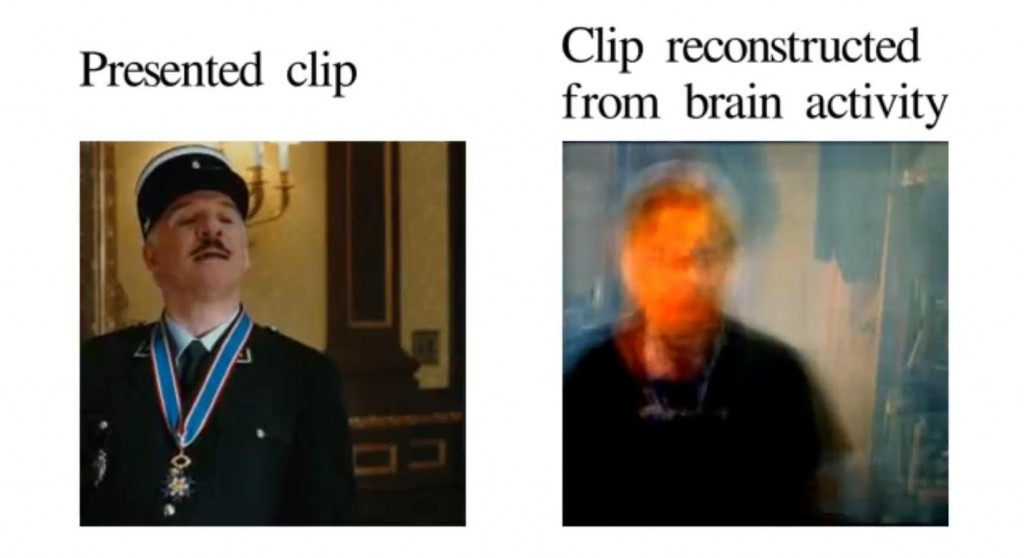

In their 2011 journal article Reconstructing Visual Experiences from Brain Activity Evoked by Natural Movies Shinji Nishimoto (another neuroscientist) and his colleagues based in Tokyo reported findings from an experiment on the transformation of brain activity into moving images. Using fMRI technology, the researchers measured oxygen levels in blood supply to the brain cortex of human subjects watching a set of trailers and short movie clips. Unlike the more recent study described above, the subjects were awake throughout the experiment. Using recordings of brain activity, Nishimoto and his associates created a computational model to reconstruct the movies. Movies clips reconstructed from brain activity are available online and remarkable, not only in terms of their resemblance to the original clips but also because the reconstructions have an ethereal dream-like quality and constitute aesthetic objects in themselves. Moreover, in the conclusion of the article the researchers state that their modeling framework could be used to decode dreams and hallucinations.

The reconstructed movie clips from Nishimoto’s study also bear a close resemblance to the dream sequences in the 1991 science fiction film Until the End of the World (UTEOTW) directed by Wim Wenders. During film production, Wenders carried out extensive research on the depiction of dreams in previous films made by other directors. He was disappointed and concluded that none of the earlier attempts looked even remotely like a dream. Instead, filmmakers relied on tropes such as smoke, blurred images, and sound cues to denote dream experiences. Interestingly, Wenders and other members of the film production team travelled to Japan to use the very latest digital technology developed by NHK (Nippon Hoso Kyokai, translated as Japan Broadcasting Corporation) and Sony to create the dream sequences for UTEOTW. At the time, digital equipment for making and editing high definition films was not widely available. Wenders recognized the potential of digital media for creating images very different to those obtained using conventional media such as celluloid film or standard definition video tape.

Surprisingly, despite obtaining access to the very latest technology for creating high definition film, Wenders proceeded to use filters to artfully distort and degrade the resolution, colour, movement, and texture of the digitally recorded dream sequences. Moreover, he looked to non-filmic sources, including oral accounts of dreams in aboriginal culture and the portrayal of light and human figures in paintings by seventeenth century artist Johannes Vermeer, as sources of inspiration for crafting digitally rendered images into dream sequences. Although Wenders collaborated with technicians, camera operators, and many others professionals with skills associated with filmmaking to depict dreams in UTEOTW, I haven’t found any evidence he consulted scientists. Further, the fictional scientist Dr Henry Farber (played by Max von Sydnow) who creates the device for recording dreams in UTEOTW is portrayed as obsessive, hyperrational, emotionally detached, and isolated within the confines of his subterranean laboratory. In many ways, Farber resembles the stereotypical ‘mad scientist’. The main cause of Farber’s negative traits is his single-minded pursuit of new technology to harvest images gathered by his son and others in order to transfer them directly into the brain of his blind wife.

The decayed hyperrealism of dream sequences in UTEOTW encapsulate Wenders’ concern and warnings about the extent to which images permeated Western culture in the late twentieth century. He believed the proliferation of images had a profoundly corrosive and dehumanizing influence on viewers. Wenders was particularly critical of the ‘stupefying effect’ of images disseminated via commercial television channels and films intended for mass audiences. These concerns are conveyed not only in interviews with Wenders but also in the radiant and melancholy dream sequences of UTEOTW. Narration, sound, and music are also used to great effect in presenting the dream sequences as enigmatic and ethereal insights (literally) into the subjectivity and personal memories of characters in the film.

There are notable similarities between the movie reconstructions of brain activity made by Nishimoto’s research group and the dream sequences created twenty years earlier by Wenders. In addition to rendering people, objects, and environments as continually shifting arrays of colour and texture that oscillate between indistinct and recognizable, the technology employed in the scientific experiments described above and in the fictional world of UTEOTW was used to record brain activity linked to subjective experiences and translate the recordings into images.

Many other science fiction and entertainment films from other genres such as film noire, horror, avant-garde, and musicals contain dream sequences. Rather than attempt to analyze a comprehensive sample here, it’s perhaps more productive to examine one such film that constitutes an elegant example in its own right, a counterpoint to the approach taken by Wenders, and a striking contrast to the dream-like reconstructions of brain activity in the experiments described above.

Hitchcock’s film Spellbound was released in 1945 and contains a short two minute dream sequence that has been widely celebrated and discussed by critics, audiences, and scholars. After undergoing psychoanalysis, movie producer and studio executive Donald O. Selznick was keen to make a film extolling the virtues of psychoanalytic therapy. He enlisted Alfred Hitchcock to direct the film, which was loosely based on a psychological thriller novel The House of Dr. Edwardes. Surrealist artist and cause célèbre Salvador Dalí was hired to create a dream sequence that was a pivotal to the film plot. As far as Selznick was concerned, hiring Dalí to work on the film was largely a publicity stunt. Hitchcock had other reasons for collaborating with the artist. As with Wenders, Hitchcock was weary of seeing dream sequences in Hollywood movies that relied on all too familiar tropes such as smoke, blurred images, and montages. He wanted to avoid using the same techniques used in the opening scene of, for example, Strange Illusion (1945) or montage sequences in the style of director Slavko Vorkapić. Instead, Hitchcock turned to Dalí for aesthetic reasons such as the ‘architectural sharpness’ of Dalí’s paintings. In an interview with director François Truffaut, conducted in 1962, Hitchcock explained why he chose Dalí to design the dream sequence “Chiroco has the same quality, you know, the long shadows, the infinity of distance, and the converging of lines of perspective.” In contrast, Hitchcock chose cameraman George Barnes to shoot all the other scenes because he was skilled in creating images that had a diffuse silvery glow when projected onto on the cinema screen.

Both Wenders and Hitchcock resisted conventional styles of visualizing dreams on film, and one of the ways they accomplished this was to contrast the aesthetic properties of the dream sequence with the rest of the film. Curiously, Wenders shot the UTEOTW dream sequences in high definition and then used various techniques to distort or, if you will, corrupt the images, which served as an allegory for their hypnotic and destructive power. Conversely, Hitchcock shot the bulk of Spellbound using a luminescent style of imaging, reminiscent of classic films of the silent era, which were juxtaposed with the sharply focused dream sequence created by production designer William Cameron Menzies, based on Dalí’s original designs. Wenders did not consult scientists or medics for advice on how to depict dream images on screen. In contrast, Selznick hired his psychoanalyst Dr. May Romm as a consultant on the film, though Hitchcock ignored virtually everything she suggested. The perceived authenticity and entertainment value of dream sequences does not rely on scientific theories or advice from scientists who specialize in recording and decoding dreams.

I hope I’ve shown the portrayal of dreams sequences in scientific work and entertainment media constitutes a fascinating topic that warrants further study. Dreams are an integral component of sleep and waking life. Humans and other species start dreaming early in life. Evidence suggests foetuses dream in the womb. Although there is an overwhelming emphasis on visual aspects of dreams, other sensations are experienced during dreams. People who are congenitally blind have regular dreams that are rich and complex but devoid of images and, instead, comprised entirely of sensations based on hearing, touch, smell, taste, and kinaesthetic (body movement) experiences. As with audiovisual dreams reported by sighted persons, blind people experience complex dreams that usually relate to recent activities, thoughts, aspirations, and anxieties. Although I did not examine the role of sound in the movies explored above, Wenders, Hitchcock, and other filmmakers were acutely aware of the importance of sound and music for creating compelling dream sequences for cinema audiences. Further, neuroscientists working on decoding brain activity have developed models to reconstruct speech based on recordings of activity in the auditory cortex of the brain. The results are no less haunting than visual reconstructions of dreams produced in laboratories and commercial film studios. It’s important to not overlook dreams are created by people and the meanings we ascribe to dreams are deeply embedded in our identity, history, culture, and imagination.

Follow

Follow